Six Sigma: Lessons from Deming

Six Sigma captured the imagination of CEO’s around the world. There have been many claims of its successes yet these have at least partially been attributed to the Hawthorne Effect 1. The Hawthorne Effect implies that if enough money is thrown into any methodology, at least some short term results might be expected. However, an increasing number of articles such as those in Fortune2, The Wall St Journal3 and Fast Company 4 suggest that Six Sigma companies are failing. The share market performance of many companies including Ford, General Electric, Motorola, Delphi, Home Depot, 3M, Eastman Kodak, Xerox and Larson, has fallen dramatically and 91 percent of companies have trailed the S&P 500 since adoption of Six Sigma.

Individual examples include the Detroit News description of quality problems with the new Ford Edge, despite Ford Motor Co having trained 10,000 six sigma blacks and having spent hundreds of millions of dollars on six sigma. Their quality problems necessitated Ford to recruit quality expert Kathi Hanley away from Toyota Motor Corp. Hanley pored over the Edge and found more than 70 significant issues and hundreds of minor concerns. In service industries, the only company to have won the Malcolm Baldridge Award twice, is the Ritz-Carlton, a company whose success is based on TQM. This may be compared to Home Depot, a company with falling profits and what has been described on NBC4 as "Worst Service Ever" - a Six Sigma company. What has gone wrong with Six Sigma and what lessons can be learned from the past, particularly from quality gurus such as the great Edwards Deming.

The appeal of Six Sigma to management was a change from the perhaps rather nebulous "continuous improvement" to a specific target of 3.4 defects per million operations. "3.4" provided both a carrot and a stick as well as a means of comparing processes and competing companies. The appeal was irresistible to thousands of companies, who jumped onto the Six Sigma bandwagon unquestioningly, despite a focus on defect reduction being criticised by Deming 5 page 9-11.

As few as 3.4 defects in a million operations, superficially seemed the ultimate in quality and for many it seemed unattainable. For service industries it was. The very best that humans can do is about 5 errors in 1000 operations6, in other words about 5000 dpmo. Service industries account for 78% of US economic output and a similar percentage of employees. Hence, for the vast majority of employees, 3.4 dpmo is meaningless. However, even for non service industries there are much more serious problems.

A "defect" occurs when a product doesn’t meet its specification. The most obvious way to reduce defects is to change the specification. A broader specification means fewer defects. This may sound silly but it is exactly what was advocated by the founder of Six Sigma, Bill Smith 7. Deming’s approach to quality was to reduce variation. Smith suggested that changing the specification "influences the quality of product as much as the control of process variation does". Six Sigma’s basis in the product specification is perhaps its most fundamental flaw.

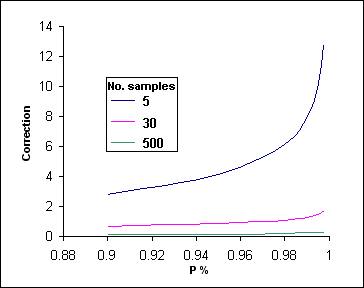

3.4 itself is a curious number. Why not zero or some other number ? "Sick Sigma" gives a detailed description of the origins of "3.4" 8, 9. In summary, Bill Smith obtained the number in error and used it in a comment about uncontrolled processes. Mikel Harry then "proved" the number as a "drift" that all processes experience (Fig 1). Harry based his "proof" on errors in the height of stacks of discs, which of course bears no relation whatsoever to processes. He later said that it was "empirical" and not needed. In 2003 Harry pulled a new "proof" out of the ether on a completely different basis and this time called it a "correction" (Fig 2). Harry’s partner Reigle Stewart changed the "proof" again to be a "dynamic mean off-set". All of these "proofs" are easily shown to be invalid 9.

While the fundamentals of Six Sigma may be flawed, consultants will claim that it is more than just a methodology focussed on defects and more than just the nonsensical 3.4 dpmo. It is claimed by Six Sigma experts that Six Sigma is "80% identical to TQM" 10, so what are the differences ? Perhaps the most easily recognised difference between Six Sigma and Deming’s teachings, is the Six Sigma’s belt system. Black belts are given responsibility for assigning improvement projects. Deming suggested that quality "was everyone’s responsibility" and at the same time most companies had quality experts in the form of quality engineers. A quality engineer had several years training compared to six sigma’s highest level of belt, the black belt, with typically only four weeks of training. With this meagre level of training, a massive level of responsibility for achieving hundreds of thousands of dollars cost savings is assigned to the black belts.

Six Sigma’s system of belts, with black, green, yellow and more recently, white belts, has been criticised both because it builds elitism. Deming stressed the importance of "breaking down barriers". Deming stressed the importance of people working together as a team rather than being directed by an artificial, poorly trained hierarchy of people holding belts. Every team member should be encouraged to educate themselves. It is often the operator that spends all day every day at his station, who has the greatest knowledge of his machine and greatest potential contribution to quality improvement and cost savings.

Deming placed great importance on pride of workmanship in achieving good quality. He pointed out how both management and workers had become a commodity to be bought or disposed of. How can employees take pride in their work when the numbers are more important than quality ? He stressed the importance of learning the psychology of individuals and groups. By contrast, Six Sigma has returned quality thinking to the days before Deming. As Mikel Harry states10 "In short, numbers-oriented thinking applies to people as much as it applies to processes and products." Treating people as numbers rather than individuals is indeed short sighted. It may or may not give short term gains but a lack of caring for people and treating employees as commodities, will lead to a company’s downfall.

Deming stated that everyone should work towards improving quality. He stressed the importance of individuals to a company’s success. This may seem like common sense but six sigma focuses its attention on an elite band of people holding belts and disregards what Mikel Harry refers to as "the masses". Such an approach alienates the workforce. It is contradictory to modern thinking incorporating an emotionally intelligent approach to management. Every employee is important to a company’s success and every employee should be appropriately trained and supported. As the world’s leader in emotional intelligence, Daniel Goleman states 11: "To the degree your organizational climate nourishes these competencies; your organization will be more effective and productive. You will maximise your group's intelligence, the synergistic interaction of every person's best talents."

A defining characteristic of Six Sigma has been its wealth of superlatives and exaggerations such a "breakthrough strategy" and "transformation". The basis of this "breakthrough" is described by Mikel Harry: "In contrast with TQM, Six Sigma operates on a very simple principle. Whatever you do to improve quality should simultaneously and immediately improve the business in a visibly, quantifiable, and verifiable way." This is decidedly deceptive. Deming states on page 1 "Productivity increases as quality improves". Deming clearly described how business success was based on quality. This has been demonstrated by the rapid rise of Deming orientated companies such as Toyota. "Everyday I think about what he meant to us. Deming is the core of our management." - Dr. Shoichiro Toyoda, (Founder and Chairman, Toyota Motor Corporation). Motorola’s winning of the Malcolm Baldrige Quality Award in 1988 is often cited as an example of Six Sigma’s success, however in reality it was 8 years of TQM programs that led to this award 12. Incidentally, "TQM" is often used synonymously with Deming, however Deming did not use this term in his teachings.

Six Sigma’s superlatives and wild claims themselves are in marked contrast to Deming’s "eliminate slogans and exhortations". Strangely, Mikel Harry claims that slogans such as "zero defects" are "devoid of meaning" yet at the same time Harry claims that "3.4 defects" is not. In reality neither Phil Crosby’s "zero defects" nor Six Sigma’s "3.4 defects" have any real meaning because defect levels depend on where specification limits are chosen. Deming stressed "Focus on outcome ( management by numbers, zero defects, meet specifications ) must be abolished …" 14 page 54

Numbers orientated thinking is central to Six Sigma and a major difference with Deming’s teachings. Six Sigma preaches Management by Objectives with a target of 3.4 defects per million. This is a retrograde step to a management style of the 1950’s, first outlined by Peter Drucker 13. Deming gives dozens of examples of how this simplistic style of management doesn’t work. "A numerical goal leads to distortion and faking, especially when the system is not capable of meeting the goal." 5 A person must have numbers to show, so he/she churns out the required numbers by whatever means is most convenient. Pride of workmanship and quality disappear. Perhaps it is more difficult for simplistic managers to understand, that if the system is corrected, good numbers will flow automatically. However only by understanding this basic principle, can there be an outcome of real quality and business success.

A shortcoming of Six Sigma has been its focus on defects without considerations of waste reduction. This has led to the growth of "Lean" or "Lean Sigma". Again we should turn to Deming. While it is widely known that Deming stressed the importance of reduction of variation, he states quite clearly that the reason productivity increases as quality improves is that there is less waste 14 page 1. This means less waste of both man hours and machine hours, leading to the manufacture of improved products and services.

Deming’s 8th point in his 14 Management Points is "Drive out fear". By contrast, Six Sigma promotes an environment of fear, as Mikel Harry states: "The key is to make fear a driving force" 10. Modern thinkers such as Goleman describe fear as a "negative" emotion and a long term "demotivator", despite possible short term gains. Fear is the easiest of motivations to instil yet the least effective 15. It results in inner anger and resentment. The most effective form of motivation is causual, where people are motivated to work for a cause or something they believe in. This can only happen when all employees are respected, trained and work to a common goal. This can only happen by driving out fear, by allowing employees to feel secure, to ask questions, to grow their knowledge, to feel respected.

Both Six Sigma and Deming describe the importance of leadership. Six Sigma’s approach is to establish a hierarchy of belts, with management by objectives, fear and numbers. Deming pointed out how management is responsible for "the system", an area responsible for 90% of problems "Don't blame the individual, fix the system for them." Deming described a ongoing cycle of continuous improvement whereby this can be achieved, rather than Six Sigma’s single cycle.

Most Six Sigma programs include hypothesis testing. In stark contrast, Deming uses this as an example of "poor teaching of statistical methods" 14 page 131. He stated that hypothesis testing has no application in analytical problems in science and industry. The reason for this difference, is that six sigma fails to differentiate between what Deming called Enumerative studies, and Analytic studies. The aim of an Enumerative study is a description of a fixed "frame" of material. The material is sampled randomly and assumed to fit some particular distribution. Hypothesis testing is a valid technique in Enumerative studies such as surveys or psychological tests. It is perhaps no coincidence that the latter field is where Six Sigma’s proponent, Mikel Harry has his tertiary education.

An Analytical study aims to improve the process that creates the material, usually while material is being produced continuously. Shewhart pointed out that the form of the distribution of data will always be unknown and random sampling does not have the same meaning as in an Enumerative study. Without a probability model, hypothesis test become meaningless. For example, consider that historical data for two processes, A and B, are compared and A appears better than B at a 90% confidence level. However at a 95% confidence level, there is no apparent difference. This is confusing enough but even worse, it gives no indication whatsoever as to future behaviour of the processes.

Enumerative studies and hypothesis tests dispose of the time element of the data. The results are purely historical and make no prediction as to future behaviour. Shewhart’s control charts are quite different in that they provide an inference to the future. The future behaviour of an in-control process is predictable, while an out of control process is not.

Six Sigma’s lack of differentiation between Analytical and Enumerative studies has lead to a false belief that control charts are based on the normal probability model. Common statements taught in six sigma classes such as "99.7% of points lie within control limits" are quite false. Deming described how this "derails effective study and use of control charts" 14 page 335. While having a validity in statistics, Shewhart control charts are based on economics. Control limits are intended to give signals as to when it is most economic to investigate special causes.

Six Sigma has introduced other dubious statistical practices such as the overlaying of normal distributions on histograms of process data, something that Deming would have scoffed at. Wheeler16, 17 has shown that such attempts at distribution fitting are meaningless. He has shown that 3200 data points are needed to fit a distribution out to only +/-3 sigma and the distribution is likely to change with time anyway 17 page 36. Even worse, attempts at distribution fitting distract users from the real purpose of process data histograms, as a tool to gain a better understanding of the process.

The "Seven Tools of Quality" are widely associated with TQM. The group of seven tools are attributed to Kaoru Ishikawa: "The seven QC Tools, if used skilfully, will enable 95% of workplace problems to be solved". The seven grew to 14 with the seven "new" tools and has continued to creep to up to the 40 or so seen in Six Sigma programs today. Deming mainly used the key tools: Cause & Effect; Pareto; Flow Charts, Histograms, Run Charts and Control Charts. More tools do not imply better quality. Given the widespread misuse of statistics, it is surely better to learn to use the primary tools correctly.

In summary, Six Sigma programs have a great deal to learn from Deming. While Six Sigma may be "80% TQM", the remaining 20% needs a great deal of improvement, from both a viewpoint of statistics and management. As long as companies are managed on the basis of a poor understanding of the analysis of data and a poor approach to working with people, Six Sigma companies will continue to fail.

=========================

Fig 1

The consequences of Six Sigma’s +/-1.5 sigma "drift" that Mikel Harry claims for every process – a process wildly out of control.

=========================

Fig 2

Mikel Harry’s 2003 attempt to justify his new +/-1.5 sigma "correction". He arbitrarily chooses the pink line at 99% to get "1.5". By choosing other plots and P values, a wide range of other "corrections" are possible. In reality control charts are not probability plots and NO correction is needed.

=========================

References:

1. Lean Six Sigma - An Oxymoron? by

Mike Micklewright2. "New rule: Look out, not in." Betsy Morris, Fortune July 11 2006

3. "The 'Six Sigma' Factor for Home Depot" Karen Richardson, The Wall St Journal,

4.

"Six Sigma Stigma" Martin Kihn, Fast Company, September 20055. Deming, The New Economics, 2d edition, p.31

6. Error rate studies:

http://panko.cba.hawaii.edu/HumanErr/Basic.htm7. "Making War on Defects", Bill Smith, Motorola. IEEE Spectrum 1993

8. "Sick Sigma" Dr A Burns. Quality Digest. April 2006 : http://qualitydigest.com/IQedit/QDarticle_text.lasso?articleid=8819

9. "Sick Sigma Part 2. Tail Wagging Its Dog" Dr A Burns. Quality Digest. Feb 2007 :

http://qualitydigest.com/IQedit/QDarticle_text.lasso?articleid=11905

10. Mikel Harry

http://www.mikeljharry.com/story.php?cid=611. Daniel Goleman. "Working With Emotional Intelligence"

http://www.danielgoleman.info/workplace/index.html12.

"The Mist of Six Sigma" Alan Ramias , BPTrends October 2005.13. " The Practice of Management" Peter F Drucker, 1954.

14. "Out of The Crisis" Edwards Deming. 1982

15. The Neilson Group

http://www.nielsongroup.com/articles/articles_climateformotivation.shtml16. "Advanced Topics in Statistical Process Control" Donald Wheeler. SPC Press 1995

17. "Normality and The Process Behaviour Chart" Donald Wheeler. SPC Press 2006